Organizational Heartbeat

I am working on a book about agency, and the power and requirements for transformational change. This comes out of about a decade of writing about philanthropy – both for effective donors and the sector as a whole. Today, Eugene Kim posted to Facebook a link to a groupaya post, How Can We Make Nonprofit Consulting Transformational? And this reminded me of Geoffrey West’s TED talk on The surprising math of cities and corporations.

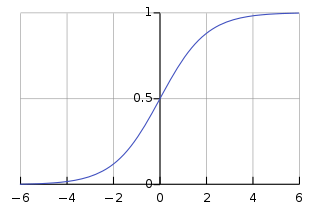

My sense is that the larger the organization, the slower the heartbeat of the organization – AND the less it is capable of transformational change. This is all about efficiencies of scale. And you know from previous posts that I have an allergic reaction to scale as a lauded idea in and of itself. It always, to me, requires clarification. Mostly because people act as if scale operates as a power law – when I think it is a sigmoidal function. Probably because of that West TED talk, of course, since I am not a mathematician by any stretch of the imagination.

West makes clear is that companies grow on a sigmoidal curve – an S curve. You grow on an s curve too. And then you stop growing. These economies of scale are not infinite. At a certain point the energy required to transmit information throughout the organization and engage all the people in it exceeds the effectiveness gained by adding more people to it. [See also what West says about cities not being sigmoidal.]

Let’s be a little more clear about this scaling thing. The Long Now has a lovely essay on West’s work, which I pulled this quote from:

Working with macroecologist James Brown and others, West explored the fact that living systems such as individual organisms show a shocking consistency of scalability. (The theory they elucidated has long been known in biology as Kleiber’s Law.) Animals, for example, range in size over ten orders of magnitude from a shrew to a blue whale. If you plot their metabolic rate against their mass on a log-log graph, you get an absolutely straight line. From mouse to human to elephant, each increase in size requires a proportional increase in energy to maintain it.

But the proportion is not linear. Quadrupling in size does not require a quadrupling in energy use. Only a tripling in energy use is needed. It’s sublinear; the ratio is 3/4 instead of 4/4. Humans enjoy an economy of scale over mice, as elephants do over us.

With each increase in animal size there is a slowing of the pace of life. A shrew’s heart beats 1,000 times a minute, a human’s 70 times, and an elephant heart beats only 28 times a minute. The lifespans are proportional; shrew life is intense but brief, elephant life long and contemplative. Each animal, independent of size, gets about a billion heartbeats per life.

Picture a mouse trying to do a startup pivot. Now try to imagine your favorite large scale organizational gorilla trying to pivot. The larger the company, the more difficult it is to turn the entire company on a single point and do something related but quite different.

Startups often go through multiple transformations of what they do, how they do it, and who they do it for. Their organizational heartbeat is fast and their scale is small. (And some of them get successfully gobbled up by the larger organizational bodies, but we can talk about that another day.)

You can have nonprofits, whose social mission talks about transformational change, hiring consultants to help them do that as much as you want, but they won’t be very good at it. The kind of organizational heartbeat needed for transformational change – that leading edge early adopter game changing innovation in the social sector – well, it isn’t going to happen in the large organization. (We could talk about how big donors impede that, how organizational mission moves from “change” to “keeping the org alive” or how larger orgs attract stable-present-focused people who aren’t keen on transformational disruption, etc… but understanding the why doesn’t change that it happens. And we ought to just be honest about it and stop speaking transformational change in organizations that don’t do it.)

Do you think organizational scale relates to ability to be transformational? Or not? If not, why not?

ps. the antidote or innovation that can disrupt this exists – organizational slime molds… crowdfunding transformational change experiments, etc. I don’t have clear answers on how that all works, but I am deeply curious about how it is connecting.

Every discrete, discernible entity will senesce and die. I suspect it has to do with their contiguity as discrete entities. By contiguous I mean you don’t exist in multiple parts with an air gap between them, and if you are disconnected that way, the part (or the rest of you) tends to stop working.

Federations are different, because they’re redundant systems of individuals that communicate with language, such that if an individual is lost, the system reconfigures to adapt. The result is the Ship of Theseus effect, wherein the components of a system are replaced incrementally, such that the system as a whole retains its identity.

Of course, corporations are comprised of people, and people are comprised of cells. Both can be understood as federations—people join and leave companies just as cells divide and self-destruct. But something is different. People and companies have discrete identities. They have body plans. Organs. And organ failure is almost always fatal.

The contrast of the federation (city, beehive, coral reef) is that it has no concept of gross anatomy. Likewise, the boundary between it and not-it is not so clearly defined. (Of course, people try to impose boundaries on them, but they tend to be tenuous fictions.) The federation’s exponential growth is also space-filling, rather than expansive. It grows richer and more complex, far faster than it gets physically bigger. My hypothesis as to what makes federations immortal is that they take the time dimension into account, existing more as stochastic processes than platonic forms. Rather, the identity of the federation drifts along as time progresses.

What West demonstrated (in spite of his own words at TED) was that what we mean when we say growth is broken. At least in the mainstream. Because we are unequivocally talking about naïve, Cartesian, expansive growth. Growth that can be measured in employee headcounts, income statements and GDP. That is precisely the kind of growth that falls along the sigmoid curve—the kind which will eventually taper off and cease.

Furthermore there are some who suggest that contraction is the antidote, because contraction is the opposite of expansion. Hair-Shirt Green, as Bruce Sterling calls it. To paraphrase: our dead great-grandparents are doing a better job at conserving energy, carbon sequestration and recycling than we are—they’re made of carbon, buried underground in a box, literally being recycled. I agree with him completely. While I believe it important to be conscientious of our consumption, I’m more inclined to save the dead-person behaviour for when I’m dead.

Instead, I prescribe a slight course correction in the concept of growth, from expansive to space-filling, from Descartes to Mandelbrot. Grow indeed—grow wiser, subtler, more elegant. Don’t just grow bigger.

Many years ago I had someone describe change in organizations of varying ages as trying to change a person based on their age. It doesn’t mean that older organizations won’t or can’t change, but just like an older person trying to change, it may just be more unusual or more complicated or take more time. And that’s been my experience.