THRIVABLE SOCIETY JOURNAL

ISSUE: WINTER 2023

Collective Intelligence: Swarms, Molds, and Forest Webs

By Jean M. Russell

Thrivable Society Journal

Winter 2023

Starling murmuration at sunset Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Studland_Starlings_%28209948269%29.jpeg

I remember being captivated by the notion of swarms. People would share a video of a starling murmuration and explain the very basic principles by which many “agents” could be acting independently and yet create something so magnificent: all the birds moving together as a whole. It spoke to a sense of belonging that I was yearning for mixed with a shared game or simple known rules. How could we move together the way the starlings moved together without bumping into one another actually or metaphorically or even emotionally. What a beautiful dance. Yes. And the sound! A murmuration is named after the sound of such a large collective as it hums! How can we humans be more like that swarm together? Humming. It was so alluring, how could I not want to be part of every swarm of birds, school of fish? How could humans be more like swarms? How could we, as groups of individuals acting in concert, jump into a layer of collective being?

Later I found that swarms and even murmurations are often largely understood to be a protection strategy. Do we just not have information in our computer models about social pleasure in a dance? The joy of friend greeting friend? There are many models of collective surviving, but where are the models of collective thriving?

With some disappointment, I filed the behavior of starlings away. Still, murmurations have inspired me to see the collective action. What is possible?

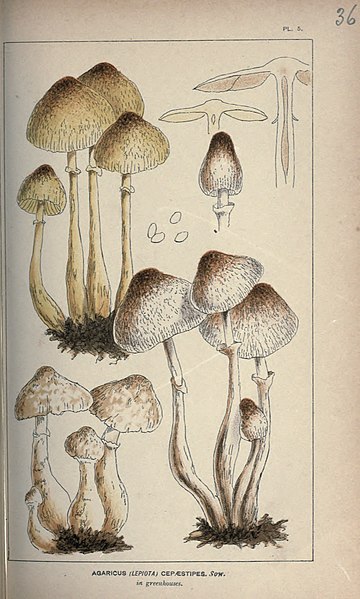

Slime Molds

A few years later, I heard David P. Reed talking about the transformation of slime mold, and I asked him to add a bit to the Thrivability Sketch. I started exploring it deeper. This too was many “individuals” acting in concert. And, the collective was so significantly different from the individual state, that they had appeared to be different species altogether. Imagine that! Imagine if the birds didn’t just maintain some set distance from each other in a murmuration but actually touched wings and turned into a Mega-Bird! “Autobirds, transform and roll out!” But this isn’t the Transformers. My flight of fancy goes too far, this is about slime molds, which do transform, though. And they do so in response to shifts in their environment: temperature, chemicals, food.

In turning the focus of collective intelligence from Swarms to Slime Molds, we increased our awareness of how a collective can be responsive to its environment in transformational ways: not just responding to predators and threats, but to the broader environment too. Not just a group, but a whole collective body.

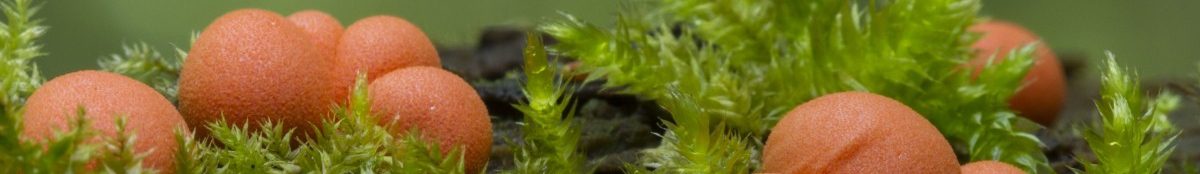

Fungi and Forests

More recently, like many of our peers, I fell headlong in love with fungi and forests. Mycelium shows collective intelligence as life forms that can find their way through a maze and increase resources directed toward successful paths and abandon unsuccessful dead ends. These collectives can probe for possibilities and respond to feedback, not just in a defensive way (away from a predator or threat) but also positively, towards more resources. We see collective intention play out. There has also been a ton of research shared in the last decade about forests: how trees communicate and care for one another (along with their alliance with mycelial networks to form forest webs). Big yes to co-building common ground for nurturance across species!

Why are these ideas so enlivening? Why does the metaphor coming from our growing understanding of the more-than-human, wild-world feel like validation for what is possible with humans? Why do they set my intuition ablaze with wonder and a sense of “follow this hunch” in my gut? (Maybe that is my own microbiome speaking up?)

Life, Death, and Centralized Control

In his essay within the Thrivability Sketch, David P. Reed wrote about alternatives to central control. “Our bias towards seeing power as a centralized phenomenon led scientists to believe that certain mold cells must be the “leaders”… but we see that “power at the edges” promotes surprising adaptability and evolvability, conferring a resilience upon the system.”

I suspect we find these wild world stories promising because they show collective intelligence that isn’t centralized command and control. They are not monumental pyramids of hierarchy, supposedly intelligent, but where the intelligence is so far from the common ground as to be alienating. Deadening for those who live within it.

If you have felt crushed by centralized control, then you might react and want to become a single agent, off on your own. Build a cabin in the woods and get away from it all. I have yearned for that. But then you or I might encounter other drivers of human behavior – like our need for belonging and our dependence on others. I can’t just escape and be content. I want to connect and cocreate. Don’t you?

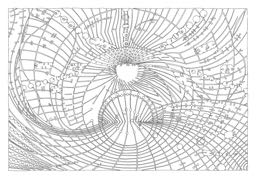

Collective Organisms

What is a way that we might coordinate human behavior without having a universal and central authority, managing our behavior? How might we balance the individual need for free will/agency/autonomy with collective well-being? How can that be as good as or better than the pyramidal centralization that successfully carried us to this level of sophistication and technological ability?

Pyramidal collective intelligence applies to large human organizations that operate through centralized decision making processes applied to top-down chains of commands.1

Some have suggested that an alternative to pyramidal collective intelligence could be holoptic collective intelligence.

From the Greek roots holos (whole) and optikè (see), holopticism means the capacity for an individual to see the whole as a living entity in the collective in which he/she operates. Sports teams and jazz bands operate in a holoptical context because each player perceives the team as a whole and knows what to do.2

A crowd is not necessarily holoptic. It is insufficient to have many together count as holoptic. Averaging the guesses of 100 players estimating the beans in a jar may seem like a kind of interesting intelligence, and there is much written about crowd intelligence this way. That isn’t the kind of collective intelligence we are looking for though (Pretend I wrote that as Obi-wan, saying it isn’t the droids.) Because the type of intelligence I am talking about isn’t computational. What the slime mold is doing isn’t the average or mean of what all the cells do. The cells literally change, like a butterfly is different from a caterpillar level change.

I am looking here for the transformation: that the slime mold and forest ecology actually transmute through an intelligence greater than what any individual knows or does. That transformation emerges from the intent of each to do something in response to what it can sense and what others do.

Better Metaphors

I want better metaphors. I believe something more is possible. These forms we are modeling, forms of distributed agency resulting in collective being; they still feel limited in function. They react. They respond. The flock of birds come together, swarm, and then dissipate. Fish, same. Their coming together doesn’t hold something more enduring than a moment for the murmuration, although the strategy helps individuals continue to live on. The slime mold and forest start to point to something bigger: redistribution of resources and cultivation of an ecology. Life giving rise to more life. This is not just the defensive signaling of one tree warning another about fire or pests, but also the movement of nutrients through the web. Now we are beginning to see that individuals can be in relation with others, without central control, and manage resources and health, even across species. Yes. And through that collective of individuals something more than the sum of the parts emerges.

How can human collectives swarm/mold/web together, not just for defense but also adjusting structure to fit the environmental conditions and moving with intention towards resources and offering invitations to other agents to join that movement on a common ground? Collective action while holding for each, as individual agent well-being. Both, and.

Yes, I want an alternative to central control and top-down management. In my heart, I want each agent to thrive in their own autonomy and capability while also having the sum of all movement be valuable, even transformational, to the whole and to each. I want to understand. I wonder, where are the models? I want to know, where have humans done this well?

Exploring the Question

So I am asking myself the question, “What does doing well look like? And, this little voice in me wanted to say ants, as they also show up in the media as interesting, around the same time. Ants! Maybe you saw the movie or even the old Ants and Grasshopper movie. So cute! [Picture one on each shoulder, talking in my ear doing a devil and angel bit.] Ants fit into this collective action picture, this social process biomimicry of the last few decades, surely. But I hear another voice in me start to scold: there is a hierarchy in the ant world. Each ant feels limited. In talking about ants, we speak of colonies of ants. And a queen who rules them all: central control. Bees too. This isn’t the kind of social structure I am yearning for. Let’s decolonize rather than model colonies. What I yearn for, deep in my soul, feels like something closer to the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (https://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/) than the nation-state of Britain.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy is one of the first and longest lasting participatory democracies in the world, bringing together multiple tribes into a peace accord. But if that analogy of the Haudenosaunee rings right, then I should probably note that the tribes of the confederacy didn’t build many huge monuments. Their “productivity” together isn’t about enduring physical structures reinforcing their prestige, making materially grand their achievements. They made common ground.3

This now, the present need I see, also seems more about an agreement to put weapons of war down and listen to our grandmothers, like the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. The Quakers have been advocating that since at least 1650.

“I told them I knew from whence all wars arose … and that I lived in the virtue of that life and power that took away the occasion of all wars, that I was come into the covenant of Peace which was before all war and strife.” GEORGE FOX (to the Commonwealth Commissioners) Journal, Vol. 1, p. 69, bi-Cent. edit. From 16504

It turns out, we westerners have long been gauging intelligence, development, and sophistication by the measure of dominance over land, other species, and other people. Now, as I think of it, that feels quite absurd. Now, as we start to unravel the consequences of that domination and what has been rendered invisible in our histories, I have serious questions.

To follow some of my flow here, it may help to wander through some reading: Survival of the Friendlist5, Humankind6 and The Dawn of Everything7 There are refreshing narratives about humans, our evolution and relationship to land, to other forms of life, and to each other. These are radical retellings from the school books that I grew up with in the 70s, 80s, and even the 90s. A retelling that puts humans as a part of nature, not apart from it.

Arrival

How did we get here? Those who can cooperate, survive against the odds. That feels plausible enough. Those who can store food for the long winter survive, for example. Those who innovate tools and technology survive. Those who can teach their offspring and relatives what they know, survive. Those who can take what they need from others, survive. Run that program for a few thousand years. Now just measure the last one as the summation of the rest: the ability to take what they need from others. That seems like how a capitalist society would see it. That is where leaning into the metaphors of nature took a wild turn to the side and assumed that lions were better for taking down a gazelle than sloths were for fitting into their ecosystem.

It is not what we take from others that fosters life8. It is where we can build common ground, upward spirals9 or life to give rise to more life. Thriving as a collective doesn’t come from domination and taking. It comes from being a contribution to something larger than oneself, building together something that nobody could do alone, growing an interactive emergent learning system that is more than the sum of the parts.

I want to roll around in a few different aspects here. Intelligence, what is it and what does it mean for us to lean into these wild world metaphors? Where can we go from there? Then I want to explore a related idea: learning systems. And finally, I want to dig into coherence: what binds people, ideas, intelligence?

Intelligence

So first, intelligence. Why haven’t we been gauging intelligence on the ability to be creative, engage in mutual aid as a resource strategy, and choose kindness over violence? In part, I suspect, because we have gauged intelligence by architecture and artifacts because of their obvious materiality. We can see it. We can see it in time, through archeology. And we can see the birds and fish, and we begin to see the slime molds and forest webs.

What if we gauge intelligence instead by the ability of life to support more life. In the human world, this might look like the ability to support the life of more people and the creature web we relate to, on the land. Of the land. What is the measure we can use that attends to the flow: the experience of abundance, rather than the stockpiling and hoarding that we recognize in monument building?

Learning

Learning

Then, second, part of this challenge feels like a system theory question. How do individual agents interact to create something greater than the sum of the parts? How does that “sum of the parts” demonstrate intelligence? Can the sum of the parts learn, except by the parts themselves? Nora Bateson coined the term Symmathesy10 to draw a distinction between living systems that learn and systems that don’t. Learning systems demonstrate symmathesy. What else is learning but the use of intelligence with memory? We can recognize learning in an agent. Can we recognize learning, as intelligence and memory, in a collective? How do we recognize and value symmathesy? How do we best assist it? What holds it together?

Coherence

And, thus we come to coherence. What brings the flock of birds together? Foiling a foe. Birds and fish and creatures that gather seem to use this as an individual and collective response to a predator or threat. We can see this often also motivates human groups: align against a common threat or enemy. Basic.

Humans, with our fancy-dance symbol-systems and sense of time, also come together as comrades for a shared purpose. This is group forming focused on building a house, saving endangered species, or creating a corporation for allocating resources. These are goal-directed groups.

They aren’t always so coherent about their why, though. Some human groups might be better described as ‘friends on a common ground,’ as Jim A. Corbett11 phrases it. Those groups hold coherence together, regardless of output, because the locus of attraction is being rather than doing. So we have: common defense, common purpose, common ground. Is this Commoning?

As we roll around in these possibly different ways of making cats of coherence, I recognize that intelligence in each might appear in rather orthogonal forms. The intelligence of being together may take quite a different form and feel quite unique when focused on a common enemy compared with the collective intelligence that arises from having outcome-focused, purposive groups managing shared resources.

Let’s draw a distinction here between a few ways we might see the intelligence of the group, given the approach to coherence the group uses. What does an individual in the group have, what do they do, and how are they being with themselves and others? And what does the group as a whole have? What does the group do? How is the group being with itself and the individuals of which it is composed? Can we recognize intelligence at the individual and/or group layer that is not a monument? What sorts of artifacts might we perceive?

You may have noted we have moved into the realms of abstraction here. I am doing so for two reasons. First, I want to know what to look for next in the wild world as a useful mnemonic metaphor for what is possible in distributed groups that demonstrate intelligence. And second, I want to see if we can get somewhere that feels appropriate to the gifts and responsibilities we have as humans and stewards of life and the land we belong to.

A Word on Nature

I have a confession here. Now. I need to admit to the romantic allure that nature holds for me. How much I want to see our next step held out to us from the wild world. And, I also want to hold a more complicated ethics. When we lean into modeling our human world on the world of birds, bees, ants, molds, lions and tigers, and other creatures, we slip into the moral codes these creatures engage with and are limited by. The wild world has a wild ethics. In the darkness, this can lead to brutality. The birds hope to avoid a predator, use this strategy to minimize their risk, but that does not mean it stops the predator. What birds try to save the ones who are caught? Do fish? What creatures not only save themselves but attempt to protect their kin? Some do, some don’t. Are we humans okay with the morality that comes with the metaphor? Do we believe we have other strategies we can use to minimize predation on our kind? From each other? I invite us to consider our ethics, of distributed collective intelligence, on the incredible ability we have to sense and feel with each other, to care for each other. What affordances do we have to enable an ethics of care appropriate to our emotional systems, intentions, and ability to communicate?

I have a confession here. Now. I need to admit to the romantic allure that nature holds for me. How much I want to see our next step held out to us from the wild world. And, I also want to hold a more complicated ethics. When we lean into modeling our human world on the world of birds, bees, ants, molds, lions and tigers, and other creatures, we slip into the moral codes these creatures engage with and are limited by. The wild world has a wild ethics. In the darkness, this can lead to brutality. The birds hope to avoid a predator, use this strategy to minimize their risk, but that does not mean it stops the predator. What birds try to save the ones who are caught? Do fish? What creatures not only save themselves but attempt to protect their kin? Some do, some don’t. Are we humans okay with the morality that comes with the metaphor? Do we believe we have other strategies we can use to minimize predation on our kind? From each other? I invite us to consider our ethics, of distributed collective intelligence, on the incredible ability we have to sense and feel with each other, to care for each other. What affordances do we have to enable an ethics of care appropriate to our emotional systems, intentions, and ability to communicate?

Common Coherence

Ethical rant complete, I want to return to what evidence we might see of common defense, common purpose, and common ground. One might say that rather than grand monuments we might look at anything we would call artificial, crafted by human hands, as the materialization of collective work. Humans come together, for purpose, common ground, or defense and we shape the world around us. We innovate tools to improve our ability to shape the world. We share what we learn from each other, and scaffold up ever more innovation. Intelligence. Learning. So I want to sense into the tools and scaffolding, even reaching up into the abstract dematerialized ones, to see what we can make possible as a collective without requiring centralized hierarchy. I say ‘sense’ rather than see, because we want to use any sort of sensing we can, every sensory capability we have, internal or on the surface, or in the space between us, to sense into this.

I am asking this question after decades of listening to our culture suggest that the development of agriculture improved humanity, and the building of the pyramids and other grand structures hold something to admire about the ingenuity of past peoples. Wengrow and Graeber12 have left me wondering, instead, if the supposed dark ages of the past actually demonstrate times in which humanity builds common ground. Maybe there is something I might admire more than the evidence of acting from common defense. I am wondering if escaping central control means letting go of the burial mounds of past oppressors as pinnacles of human achievement. I am listening to my partner’s mother idolize lost civilizations while wondering what happened to lose them. And we are seeing so much about why civilizations end, perhaps sensing our own impending demise. What else is possible?

There are hints that much of the present United States had been managed by the people who honored the land here before being invaded by Europeans. Perhaps they cultivated a common ground by coming from a place of the ground itself being sacred and belonging to the land rather than the land belonging to them?

I read about the disappearance of the commons and wondered how the nobles sold us that bill of goods, that they should privately own what had been publicly shared. Somehow it leans more into the model of central control, naming a border to a territory so it can be defended against others. Against other humans.

I snort at myself and want to avoid being so idealistic here as not to acknowledge that starvation happens or disease. We have certainly faced times where we had to find ways to choose which people survived and which did not. Who do you bring in from the cold? Does bringing them in keep you safe from their anger and fear?

And still, my intuition presses on, these times need not be the default, the norm, the way things need to be. We are told so only by those who use it to justify their own choices. The humans who give away their own coat to keep another warm don’t build monuments to their own egos. Beware of the evidence trail left behind by narcissists.

Commoning

So I want to look at commoning from the place of common ground. Is there something here to revisit in our human history? Can we find the times in our past in which individuals came together to build a shared relationship with the land and each other? Consider now that the tragedy of commons has been defeated by numerous examples documented for decades by Elinor Ostrom and her collaborators. What might we learn from her nobel-prize-winning explorations?

As a side note, I would say that the tragedy of the commons, as the story is usually told: a pasture and people choosing to optimize for their own maximal output at the expense of others and the pasture itself… is really a story about a free market without private property or governance. Actual commons have governance, and Ostrom and her collaborators have some basic rules they generalized from the successful commons they studied.

What are the better metaphors we can look to for commoning on common ground? Perhaps you can help me and us find better metaphors? My intuition is guiding me here, but I am unclear where to go next.

Where might you take it?

- How does our nesting of common grounds create a way to include those who would seek to invade? AKA, what is the strategy for defense against outsiders when the main purpose is cocreation on common ground?

- Monuments and even the religion so many monument-cultures live inside may make for a material coherence to society. What other ways might we recognize coherence, especially without hierarchy?

Flocking intelligence is the intelligence of defense. It moves away from. What are the better metaphors of life moving towards desired resources and collective purpose? - How do we develop ethical models for collective intelligence given the emotional abilities we have and how that may differ from the ethics of algae?

- What metaphors of cross-species symmathesy can we be inspired by?

- There are game theory trackers concerned about Mollach. How does collective intelligence of this transformational type steer clear of the worst possible outcomes, in the end? How is the collective intelligence game structured to not reward malicious action?

Footnotes for Collective Intelligence: Swarms, Molds, and Forest Webs

1 https://cir.institute/pyramidal-collective-intelligence/

2 https://cir.institute/holopticism/

3 There are plenty of indigenous groups who have been monument builders, so I do not mean to imply that being indigenous can be synonymous with building common ground rather than common statues.

4 https://quaker.org/legacy/mounttoby/statements/historical%20statements.html

5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Survival_of_the_Friendliest

6 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humankind:_A_Hopeful_History

7 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dawn_of_Everything

8 When we assume supremacy, we then decide what the hierarchy is based on. If we base it on who eats what, we get one perspective on life forms (predators at the top). If we base it on who proliferates, we get another (ants outnumber us all). For thrivability, let us avoid the moves of supremacy and hierarchies where we hide the decision of what we value. Let us say instead that we value life and life giving rise to life, and notice how life of all sorts and sizes does this.

9 https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/548071.Seeing_Nature

10 https://norabateson.medium.com/symmathesy-709a39ccb5bc

11 https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/76872.Goatwalking

12 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dawn_of_Everything